The Peer Review Improvement Opportunity

Full article available as PDF: Request Reprint

From QA to QI

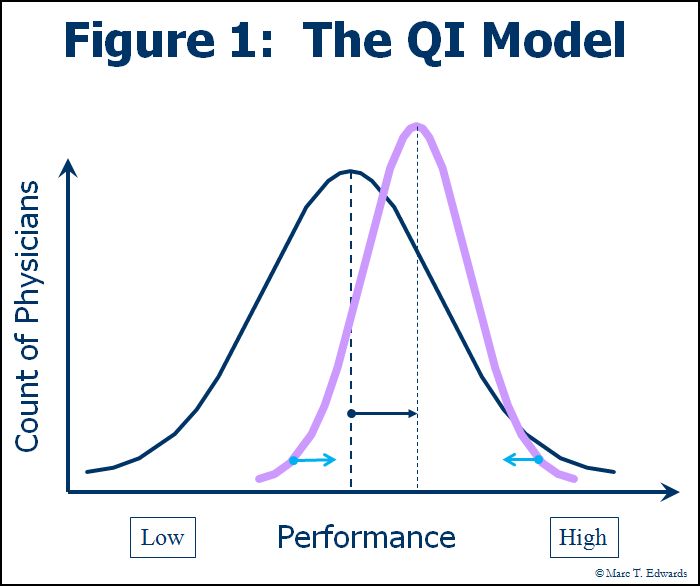

Over the past decade, hospitals have come to embrace the Quality Improvement (QI) model that successfully transformed other industries. Through a variety of tools and techniques aimed at standardizing and improving processes, QI seeks to "shift the curve" towards higher performance (see Figure 1).

The Failure of the QA Model

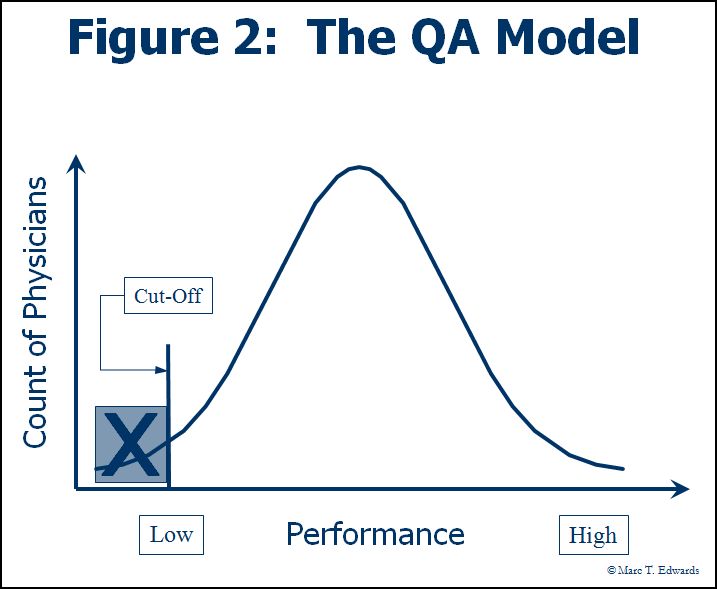

Peer review, however, remains an anachronism. It is still commonly conducted within the Quality Assurance (QA) framework. By today’s standards, "Quality Assurance" was misnamed: it hasn’t assured either quality or patient safety. Neither has it served to eliminate substandard care. The QA model presumes that problems in care delivery can be minimized through inspection of untoward events to identify the underlying failure of professional judgment. As a result, peer review has been conducted with the primary objective of determining whether substandard care occurred and, if so, who was responsible - to prevent "the bad apples from spoiling the barrel." This is tantamount to endorsing the false belief that simply trimming one tail of the distribution will substantially improve overall performance (see Figure 2). Thus, in many hospitals, peer review is rendered ineffective because it is threatening to individual careers and economic livelihood.

The other major problem with the QA model is that it confuses the evaluation of performance with the assessment of competence. Competence is an enduring quality that changes slowly over time in the absence of a major health event (e.g., stroke, substance abuse). The Joint Commission standards calling for Focused (initial) and Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (FPPE/OPPE), which became effective in January 2008, gave us a new set of buzzwords and may have inadvertently perpetuated this confusion. FPPE/OPPE is really about monitoring competence in the intervals between the mandated 2-year reappointment process. Peer review, which is fundamentally an assessment of clinical performance in a specific context, can provide important data for FPPE/OPPE, particularly in the aggregate.

If the QA model of peer review is fundamentally antithetical to our efforts to improve the overall quality of care, it is also wasteful. It captures only a small fraction of clinical performance data available to the review process. Moreover, it misses the opportunity to:

- Identify and correct problems in care processes and interfaces, which pose an ongoing threat to care quality and safety and which are 2-4 times as frequent as practitioner error

- Shift the curve of performance by providing timely and meaningful clinical performance feedback

- Leverage data from aggregate reporting and trend analysis iteratively improve both peer review process and clinical care

- Deal with the gray zone of performance below the threshold for adverse action, before a serious adverse event occurs, while the personal and organizational cost for correction is low

- Efficiently identify cases worthy of review by engaging physicians to self-report adverse events, near misses and hazardous conditions.

Given all these limitations and inefficiencies of the QA model, the potential return on investment for improvement in peer review process is substantial.

If we wanted to re-invent clinical peer review using contemporary QI principles, what would it look like?

A New Framework

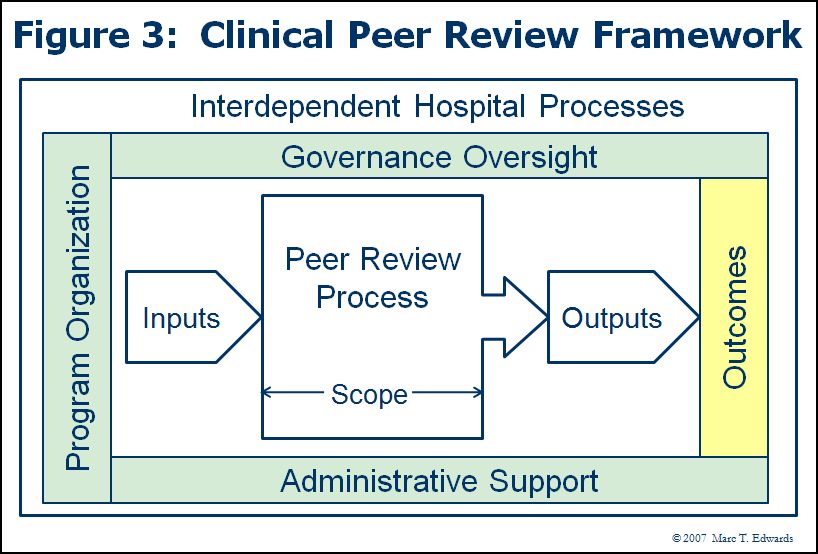

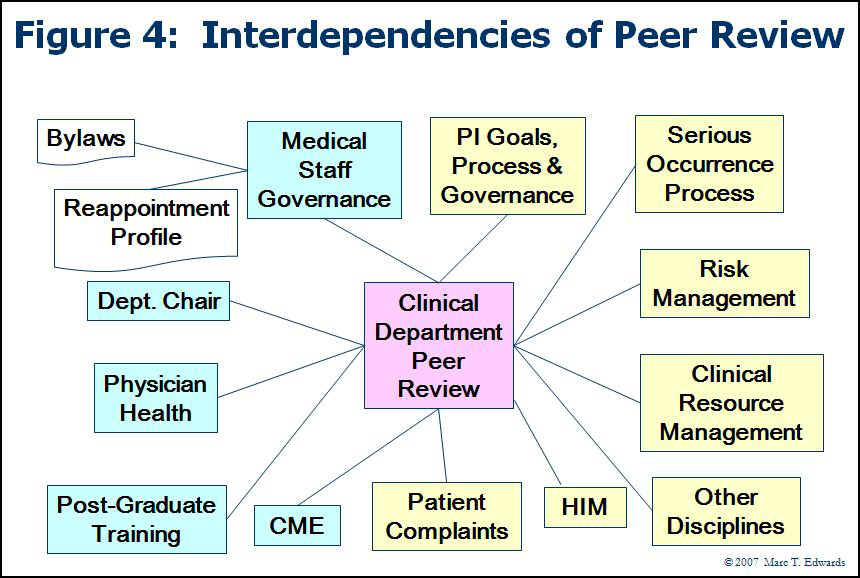

Figure 3 presents a high-level framework for clinical peer review activity. Any and all of these aspects can and should be studied for systematic improvement. Figure 4 elaborates on the key hospital processes and functions that are interdependent with peer review activity. These interfaces may also be targets for improvement efforts.

In my first national survey of peer review practices, Dr. Evan Benjamin and I applied this model to identify the key drivers of the perception that peer review has a significant ongoing impact on the quality and safety of care at the hospital. (1) The unexpected finding was that the factors we identified make intuitive sense when considered in a QI context. In other words, the more that peer review looks like QI instead of QA, the more effective it is felt to be. I subsequently translated the survey results into a 100-point, 13-item Peer Review Program Self-Evaluation Tool. (2) When applied to our original study population, the mean score was 45, suggesting huge opportunity for improvement across the country. No one scored at A-level, which may explain the dearth of examples of real success stories. The utility of the tool and the magnitude of the performance gap were subsequently validated in a different group of hospitals. (3) The follow up study also demonstrated that a well-designed peer review program can significantly influence objective measures of quality and safety. (4) In addition, it enabled a refinement of the Self-Evaluation Tool which is now available online: Clinical Peer Review Program Self-Evaluation Tool.

The Formula for the QI Model

- Distinguish between performance and competence

- View peer review as clinical performance measurement and improvement

- Aim first and foremost to improve the quality and safety of care

- Encourage clinicians to self-report adverse events, near misses, hazardous conditions and other learning opportunities related to their patients

- Measure clinical performance during case review

- Standardize review committee processes

- Rationalize the connection with the hospital's performance improvement function

- In each review, seek out whatever can be learned to improve both individual performance and the process of care

- Train reviewers, committee chairs and support staff

- Harness the power of information systems to periodically aggregate data and analyze trends

- Provide timely and balanced performance feedback, including the recognition of excellence

- Monitor the outcomes of peer review

- Govern the process effectively and continue to improve incrementally

- Keep the trustees informed of the impact of peer review on quality and safety of care

- Promote self-reporting of adverse events, near misses and hazardous conditions under the protection of a Patient Safety Organization relationship

A few comments on these points may be useful.

Relationship to Hospital QI

Peer review needs to be well-connected to the organizational quality improvement function. As a practical matter, most review committees don’t have the resources or skills to manage the process improvement stuff that can be uncovered by diligent peer review. Conversely, most hospital QI programs face limitations in terms of the issues they can surface. For example, clinician to clinician issues, the subset of system issues that figured most prominently in our regression analysis, are hard to uncover except through peer review.

Clinical Performance Measurement

In the process of case review, the many programs record an overall quality “level” and some look at component factors, but only rarely are such ratings meaningfully quantified. The scientific literatures shows that clinical performance can be measured during case review by rating multiple elements of performance having specific clinician attribution using reliable scales. This generates at least 10-fold more clinical performance data with minimal additional effort. The added statistical power and scope of the data collected lowers the cost to assess variation.

Sanazaro and Worth have shown that as few as 5 cases can reliably compare performance among physicians when structured ratings are used. (5) Please refer to my whitepaper or PEJ publication on clinical performance measurement for a more detailed discussion. (6)

Case Review Volume

A few industry pundits have been promoting centralization and reduced case review volume, but have not published data on the outcome of such changes. Our national study found a minimum threshold for review volume among the predictive factors of belief in efficacy. Also, Graber showed that broadening the scope of peer review to include a search for process of care issues quadrupled the number of problems identified and greatly magnified the number of quality improvement projects initiated. (7) So throttling back may be counter-productive.

We can also look at the review volume question from the angle of waste. Since the QA model is only focused on making the standard of care decision in the peer review process, the return on the invested effort is small. Most of the time, deviation is not significant. This is because the commonly used generic screens have low specificity even for substandard care. (8) What has been thrown away is the opportunity to actually measure clinical performance and provide the feedback necessary to “shift the curve”.

The coda on the volume question is that, over time, we need to develop good data on what would be the high payback triggers for peer review in the framework of the QI model for peer review. The most promising strategy is to promote self-reporting of adverse events, near misses, and hazardous conditions. In organizations suffering from the burden of the QA model, the concept of self-reporting might seem ludicrous because no physician would voluntarily seek exposure to criticism and blame. Nevertheless, self-reporting has been nicely demonstrated in a healthcare setting. (9) Moreover, self-reporting has had a major impact on aviation safety over the past 20 years. It was facilitated by offering relative immunity from disciplinary action. Today, the greatest leverage for comparable cultural change in healthcare comes from the Federal protections of the Patient Safety Act. By adopting the QI model and establishing a Patient Safety Organization relationship, any healthcare organization can readily promote self-reporting. (10)

References

- Edwards MT, Benjamin EM. The process of peer review in US hospitals. J Clin Outcomes Manage 2009(Oct);16(10):461-467.

- Edwards MT. Peer review: a new tool for quality improvement. Phys Exec 2009;35(5):54-59. Request Reprint

- Edwards MT. Clinical peer review program self-evaluation for US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2010; 25(6):474-480. http://ajm.sagepub.com/content/25/6/474

- Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2):110-119. http://ajm.sagepub.com/content/26/2/110.short

- Sanazaro PJ, Worth RM. Measuring clinical performance of internists in office and hospital practice. Med Care 1985;23(9):1097-1114.

- Edwards MT. Measuring clinical performance. Phys. Exec 2009;35(6):40-43. Request Reprint

- Sanazaro PJ, Mills DH. A critique of the use of generic screening in quality assessment. JAMA 1991;265(15):1977-1981.

- Graber ML. Physician participation in quality management: Expanding the goals of peer review to detect both practitioner and system error. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1999;25(8):396-407.

- Katz RI, Lagasse RS. Factors Influencing the Reporting of Adverse Perioperative Outcomes to a Quality Management Program. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:344–350.

- Edwards MT. Engaging Physicians in Patient Safety through Self-Reporting of Adverse Events. Physician Exec. 2012;38(4):46-52. Request Reprint

Links

- Clinical Peer Review Process Improvement Resources

- The QI Model for Clinical Peer Review

- The History of the QA Model

- Clinical Peer Review Program Self-Assessment Inventory

- Ideal Clinical Peer Review Process Collaborative

- Normative Peer Review Database Project

Whitepapers

Products and Services

- The Peer Review Enhancement ProgramSM

- PREP-MSTM: Program Management Software

- My PREPTM: The Complete Toolkit for Improvement

- DataDriverSM

- Client Testimonials

- Typical Client Results